Amid the brutal chaos of the Vietnam War, another deadly adversary silently loomed: malaria. With troops incapacitated by the thousands, Vietnam turned to China for help. The result? A covert initiative known as Project 523. One scientist’s ingenuity and determination sparked a groundbreaking treatment, all developed under the shadow of war and revolution.

Vietnam – Occupation and the Threat of War

From the mid-19th century, Vietnam was part of French Indochina, where local traditions were suppressed, sparking revolutionary movements. Ho Chi Minh established the Indochinese Communist Party to pursue a communist state in Vietnam. During WWII, Japanese occupation garnered support for Ho’s Viet Minh resistance from the US, USSR, and China. After the war, Ho declared Vietnam’s independence, but French forces returned, leading to the First Indochina War in 1946. This resulted in a divided Vietnam: The Republic of Vietnam in the US-backed South and the communist North, supported by the USSR and China.

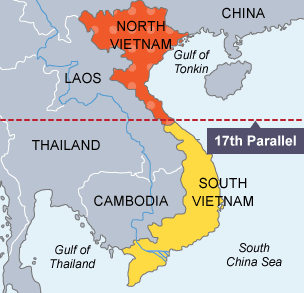

By 1954, the Geneva Conference solidified the split at the 17th parallel. Both sides held ‘elections’ aiming for legitimacy with the South reporting 133% support, while the North overwhelmingly backed Ho Chi Minh with 98% of votes returning in support. Over the next six years, the North pursued unification through several insurgencies. By 1960, the US, concerned with containing communism, escalated involvement, beginning with 16,300 troops under JFK and growing to over 500,000 under Lyndon B. Johnson by 1968.

The war was fought in the air and the dense forests of southern Vietnam, where the Vietcong’s knowledge of the terrain gave them an edge. However, this advantage came at a heavy cost, as thousands succumbed to malaria, with some battlefields seeing 90% of their forces succumbing to the disease.

Establishing Project 523

In 1967, Ho Chi Minh sought medical support from China. Although China’s leader, Mao Zedong, had just launched the Cultural Revolution—closing universities and expelling scientists—he recognised the importance of the request. On May 23, 1967, Mao started a covert military project known as Project 523 to tackle the crisis.

More than 600 scientists, medical experts, and military personnel were recruited to explore both Western and Traditional Chinese Medicines, aiming to develop treatments that would reduce deaths in Vietnam and beyond.

Mao Zedong (1893–1976), founder of the People’s Republic of China, led the nation from 1946 until his death in 1976. In 1966, he launched the Cultural Revolution, a campaign aimed at purging Western influences and eradicating the “Four Olds”: old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits.

The Cultural Revolution led to widespread book bans, imprisonment and torture of intellectuals, the destruction of ancient Chinese artifacts, and an estimated 2 million deaths.

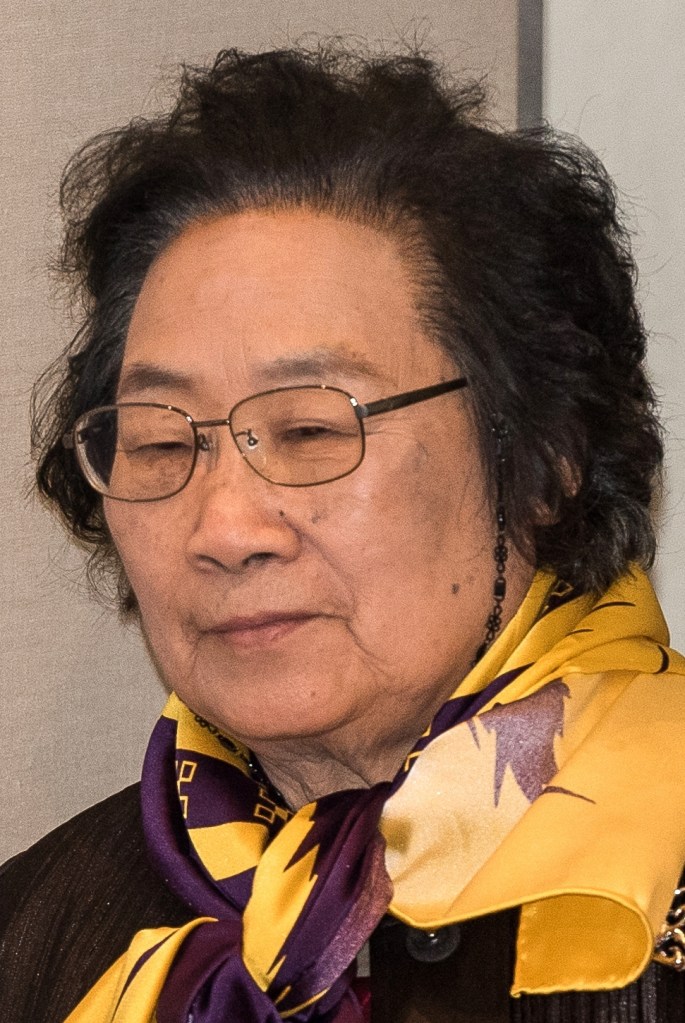

One of Project 523’s lead scientists was Tu Youyou, a young researcher whose own experience with tuberculosis in high school had inspired her medical career. After graduating from Beijing Medical University’s School of Pharmacology in 1955, she began her research at the China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, specialising in traditional Chinese medicine.

Tu Youyou

When Tu Youyou was drafted into the covert Project 523, her family life was upended. Her husband was exiled to the countryside, while her young daughter, just four years old, was left in a local nursery for months at a time. Reflecting on these sacrifices, Tu later remarked, “The work was the top priority, so I was certainly willing to sacrifice my personal life.”

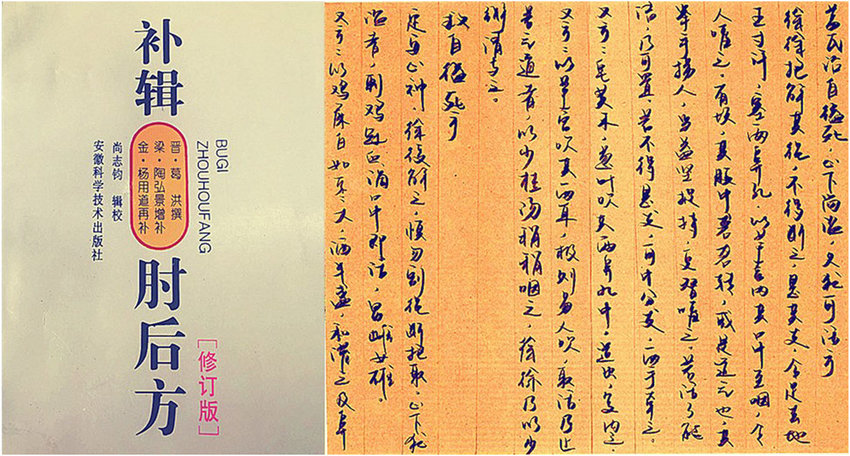

In her research, Tu turned to a fourth-century Chinese medical text, The Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies, which referenced an extract from Artemisia annua, or sweet wormwood, as a treatment for “intermittent fevers”—a term often linked to malaria.

The recipe instructed: “Take a handful of sweet wormwood, soak it in a sheng of water, squeeze out the juice, and drink it all.”

By 1971, Tu and her team successfully treated malaria in experimental mice and monkeys, leading to human trials where 21 patients were cured. They named the drug artemisinin, after the plant it was derived from. However, delivering the drug on the necessary scale proved challenging. Tu then synthesised it further into dihydroartemisinin, a more potent and effective form that surpassed traditional malaria treatments like chloroquine.

Although Project 523 was originally started for the Vietnamese, the drug’s existence stayed a secret until after the Vietnam War ended with the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. In a dark twist of fate, the drug’s first large-scale deployment was during China’s own invasion of Vietnam in 1979, spurred by Vietnam’s occupation of Cambodia the previous year. This irony underscored the complexity of international relations, as a life-saving discovery born of alliance was soon weaponised amid shifting tides of conflict.

Under the Cover of Secrecy

Secrecy laws meant that for years, the existence of artemisinin was confined to China, with scientists unable to publish their findings. In 1979, the Qinghaosu Antimalaria Coordinating Research Group formally introduced artemisinin to the international scientific community. Yet, despite malaria accounting for over 2% of global deaths, the world reacted with caution. The Cold War atmosphere hindered collaboration, and with Chinese research viewed warily, medical advances like artemisinin struggled to gain traction in the West. Scientific exchange was severely limited, leaving a critical treatment sidelined despite the disease’s staggering toll.

Project 523 was officially closed in 1981, but this marked a pivotal moment for malaria research. The Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases, backed by the UN and WHO, seized the opportunity to host the first international conference in Beijing to discuss artemisinin’s potential as a malaria treatment.

This conference sparked further advancements in antimalarial drugs, leading to the creation of a combination therapy with artemisinin and mefloquine designed to reduce recurrence rates and combat drug resistance. As the field evolved, the synthesis of this new class of medications gave rise to artesunate, the first drug developed entirely by a domestic Chinese company, symbolising a significant leap by the Chinese in the fight against malaria.

Despite the undeniable advantages of artemisinin-derived medications in combating malaria, it wasn’t until 2006 that the World Health Organisation officially recognised these derivatives as the treatment of choice through the establishment of artemisinin combination therapy (ACT). This delay underscores a complex interplay of factors, including lingering scepticism from the international community and the challenges of integrating new research into existing health frameworks.

ACT represents a significant breakthrough, combining artemisinin with other antimalarial drugs to enhance efficacy and reduce the risk of drug resistance. This multi-faceted approach not only improved treatment outcomes but also paved the way for a global response to malaria that was more adaptable and effective. As ACT gained acceptance, it catalysed a renewed focus on malaria eradication efforts, demonstrating the critical importance of scientific innovation in public health. However, the long road to recognition also highlights the barriers that can impede the implementation of life-saving treatments, often at the expense of countless lives.

Finally Receiving Recognition

As the global landscape began to shift from a culture of secrecy toward collaborative efforts for shared aims, the long-standing veil of obscurity surrounding Tu Youyou was finally lifted. This newfound openness not only illuminated her groundbreaking contributions to medicine but also prompted a broader re-evaluation of the scientific community’s recognition practices in China. Rao Yi, the current President of the Capital Medical University in Beijing, noted in a poignant blog post that “China was not paying attention to some scientists who had done outstanding work for China but had not been properly recognised for their work.”

This statement resonates deeply, reflecting the struggles faced by many researchers whose innovations were overshadowed by political and societal upheavals. Tu Youyou’s story serves as a powerful reminder of the untapped potential within the scientific community when talent and ingenuity are nurtured rather than stifled.

In the years that followed, Tu’s achievements began to receive the acknowledgment they so richly deserved, sparking a movement toward honouring scientists who had previously laboured in the shadows. Her journey from obscurity to recognition not only marked a personal victory but also symbolised a pivotal change in how China and the world approach scientific contributions, emphasising the importance of transparency, collaboration, and appreciation for those who dedicate their lives to advancing human health.

In 2011, Tu Youyou received the prestigious Lasker-DeBakey Clinical Medical Research Award for her groundbreaking discovery of artemisinin. Four years later, in 2015, she made history as the first female Chinese national to be awarded the Nobel Prize, an honour that solidified her influence on global health and scientific research. In recognition of her immense contributions to China’s scientific standing, she was further honoured with the Medal of the Republic, the country’s highest civilian accolade.

Conclusion

Tu Youyou’s remarkable contributions in the fight against malaria underscore the power of scientific ingenuity and dedication, even under restrictive conditions. Her persistence through personal sacrifices, her groundbreaking approach in combining traditional Chinese medicine with modern pharmacology, and the international impact of artemisinin serve as a legacy. The story of Project 523 reflects the ways in which innovation can arise even in times of political tension, providing a reminder that science can bridge divides and save countless lives. Tu’s Nobel Prize recognition in 2015 cemented her legacy, ensuring her pioneering work will continue to inspire future generations of scientists worldwide.