It’s July 21st 1976, and 2,000 American Legion delegates are gearing up for their annual conference at the grand Bellevue-Stratford Hotel in Philadelphia. The excitement is palpable as the attendees arrive from all corners of the country, eager to share ideas, connect with like-minded individuals, and take in the sights and sounds of the City of Brotherly Love.

But what starts out as a promising week of networking and learning quickly turns deadly. Just a few days after the conference, people start falling ill. At first, it’s just a handful of cases – a fever here, a cough there – but soon, the illness spreads like through the hotel.

Twenty-four Legioneer’s lives would be lost the week following the conference, all from a previously unknown bacterial disease that will later be named after its first victims: Legionnaires’ Disease.

The American Legion, one of the largest veterans’ organisations in the United States, was founded in Paris, France in 1919 when a group of American soldiers, who were serving in Europe after World War I, came together to create an organisation that would support their fellow veterans back home.

Since then, the American Legion has grown to have a registered members list of over 1.8 million people, making it one of the most influential organisations in the country. It’s not just ordinary veterans who are members of the American Legion. Some of the most famous people in American history have been part of this organisation. For example, both President Bushes, as well as John F. Kennedy, were all members of the American Legion at some point.

The American Legion meets for its National Convention in a different host city each year. In 1976, in order to coincide with the 200th Anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, it took place in Philadelphia at the Bellvue-Stanford Hotel.

The three-day event went off without a hitch until, three days after the event, US Army veterans, Ray Brennan and Frank Aveni both died of suspected heart attacks. In the five days following the event, 11 attendees had all passed away following complaints of fever, fatigue, confusion, headache, diarrhoea, non-productive cough, and shortness of breath.

A full week after the death of Brennan, 105 Legioneers were admitted to hospital and 24 had died.

A number of those who were sick arrived at the same hospital, with the same symptoms, all after being in the same place. The doctors looking after them informed the CDC and it fell to the desk of microbiologist Joseph McDade. He decided to start by infecting guinea pigs (why not) with lung tissue from those who became ill. As he examined the tissue under a microscope, he noticed a few gram-negative bacilli. But when he tried to culture the bacterium, it just wouldn’t grow on agar.

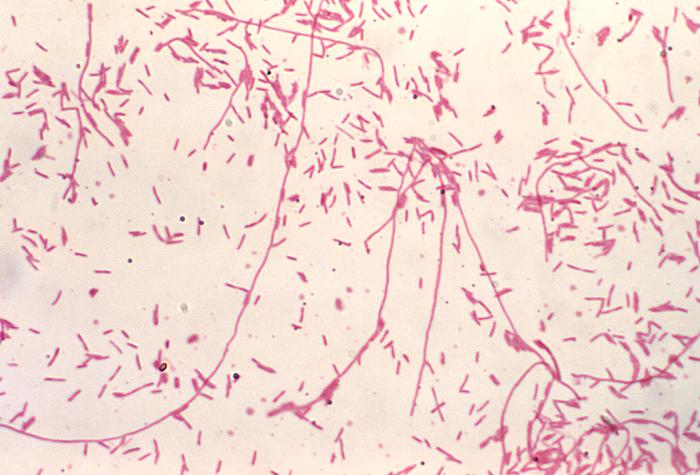

Frustrated but undeterred, McDade continued his search for answers. He attempted to isolate the bacterium in eggs, but this too failed. However, during a brief return to his lab over the Christmas break, he noticed something unusual. Infected eggs that had antibiotics omitted were showing unexplained observations. And with further investigation, he finally identified the bacteria using a Gimenez stain. It turned out that a new family of pathogenic bacteria, Legionella pneumophila had been discovered.

Gram staining, named after Danish bacteriologist Hans Christian Gram, is a method used to differentiate two large groups of bacteria based on peptidoglycan in their cell walls. Gram-positive cells have a thick layer of peptidoglycan meaning they turn violet. Gram-negative cells have a thinner peptidoglycan layer that causes the first stain to wash out, leaving only the pink counterstain.

The stain used to identify L. pneumophilia, the Gimenez stain, causes the bacteria to be stained blue in tissues.

Legionella pneumophila, is a gram-negative bacillus bacteria belonging to the Legionella genus. It is commonly found in freshwater sources as a pathogen of amoebae. However, when humans are exposed to contaminated water sources and inhale aerosols containing bacteria, they can become infected with bacteria.

Once the bacterium takes hold, it starts replicating inside macrophages of the alveoli, leading to a severe pneumonia infection that can be life-threatening. Symptoms of the disease usually develop within a few days of infection and include headaches, fevers, non-productive coughs, muscle pains, and delirium.

There is currently treatment for the disease, but those who develop Legionneers will have to attend hospital, be placed on a course of IV antibiotics and be monitored for a number of days. In countries with adequate hygiene practices, most patients will overcome their symptoms after a few weeks of treatment.

The fact that the disease can only be contracted through contaminated water sources and not from those who are currently infected added another layer of complexity to the diagnosis and treatment of Legionnaires’ disease in 1976. The question was, how did all of these people get infected?

Dr Peter Skally, another CDC scientist, conducted experiments that revealed Legionella pneumophila‘s ability to survive for extended periods in water. While there was no concrete evidence of the disease being transmitted through drinking water, scientists began considering the possibility of droplet infections as a possible mode of transport.

In due course, the source of the outbreak was traced to an infected cooling tower that supplied air conditioning to the building. The tower was emitting small droplets containing the bacteria, which were then circulated throughout the building, potentially infecting thousands.

The Bellevue-Stratford Hotel gained worldwide notoriety for the deaths of its veteran patrons, but not all publicity is good publicity. In November 1976, four months after the outbreak, and two months before the disease was identified, the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel closed its doors. It reopened two years later and, after changing hands numerous times, it is now known as the Bellevue Hotel. A four-star with rooms costing around $200 per night.

A miraculous comeback for a site of such devastation.

What’s in a name?

The disease is known as Legionnaires’ disease, named after those who died of the disease in 1976. They are also the namesake of the bacteria that causes the disease, Legionella pneumophilia. Originally, as the origin of the disease was unknown, the disease was known as “legion fever”

The discovery of the contaminated cooling tower in the Legionnaires’ disease outbreak prompted the implementation of new regulations and guidelines for managing cooling towers and other water systems. The aim was to prevent the spread of the Legionella pneumophila bacteria and mitigate the risks associated with such transmission.

In response to the outbreak, legislative changes were also introduced which have had a significant impact on reducing the number of Legionnaire’s disease cases and improving the overall management of water systems. These measures include regular testing and maintenance of water systems, which have become standard practice and have enabled organisations to identify and respond to potential outbreaks quickly.

In addition, Legionnaires’ disease is a notifiable disease in England and Wales, which requires health professionals to report suspected cases to local public health teams. This approach helps healthcare professionals identify clusters and prevent outbreaks while monitoring trends in disease occurrence over time.

Despite these measures, and 40 years of scientific advancement, Legionnaires’ disease is still prevalent in the UK. In 2018, Royal United Hospital in Bath was fined £300,000 for failing to test their water systems for the disease which resulted in the death of a patient from Legionnaires in 2015.

The lesson of the Philadelphia outbreak is clear – we must remain vigilant and work together to prevent and control the spread of new and existing infectious diseases. Science and medicine are our best defences against the invisible threats that surround us and we must be prepared to use them to their fullest extent to protect ourselves and our communities.

sources.

Cianciotto, N.P., 2001. Pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 291(5), pp.331-343.

Health and Safety Executive (2021) Symptoms and treatment of Legionnaires. Available at: https://www.hse.gov.uk/legionnaires/symptoms.htm

Kirby, B.D. et al., 1980. Legionnaires’ disease: report of sixty-five nosocomially acquired cases and review of the literature. Medicine, 59(3), pp.183-205.

Lattimer, G.L. et al., 1979. The Philadelphia epidemic of Legionnaire’s disease: clinical, pulmonary, and serologic findings two years later. Annals of internal medicine, 90(4), pp.522-526.

Public Health England (2019) Monthly Legionella Report December 2019. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/859151/Monthly_LD_Report_December_2019.pdf

Tsai, et al, 1979. Legionnaires’ disease: clinical features of the epidemic in Philadelphia. Annals of internal medicine, 90(4), pp.509-517.

Vogel, J.P. and Isberg, R.R., 1999. Cell biology of Legionella pneumophila. Current opinion in microbiology, 2(1), pp.30-34.

Winn Jr, W.C., 1988. Legionnaires disease: historical perspective. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 1(1), pp.60-81.