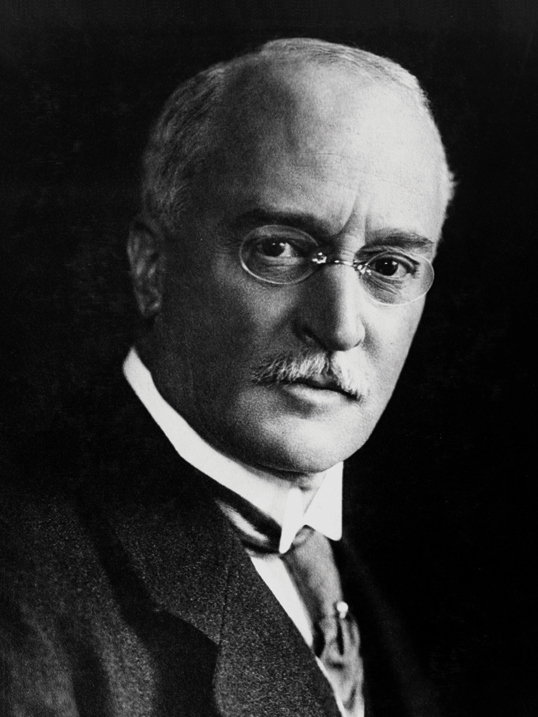

In 1892, Rudolf Diesel invented the Diesel engine. Twenty-one years after his world-altering invention, whilst on the SS Dresden sailing from Antwerp to London, he retired to his cabin around 10 pm and requested a wake-up call at 6:15 am. This was the last time Diesel was seen alive.

His room was neatly laid out, his bed not slept in, and his clothes folded on the nightstand. Ten days after his disappearance, on the south coast of the Netherlands, a body was seen floating in the water. On the 13th of October 1913, his son, Eugen, positively identified the body as that of his father.

Upon the news of her husband’s death, his wife Martha opened a bag Diesel gave her before his departure. In it were 20,000 Marks and statements of their empty bank accounts. His death remains unsolved, but for many, it is clear he committed suicide whilst aboard the SS Dresden.

What is Hinterland?

The story of the inventor of the diesel engine is not content on the curriculum but is content that skirts around the core material we are mandated to teach. Stories like Diesel’s touch upon the curriculum but add more than what is prescribed. The tales from the past and present can illustrate to pupils that science is not cold, nor is it devoid of life, but it is filled with inventions, intrigue and ingenuity whilst also being littered with deceit, destruction and death.

Are the stories of Rudolf Diesel or of Thomas Midgeley Jr. necessary for pupils to pass their exams? No. But, when teaching fractional distillation and hydrocarbons as part of GCSE Combined Science, we are looking to create young adults that foster a love for science and care about the future of the climate, and for this, Hinterland is necessary.

Let’s look at another example.

When looking at bacterial diseases in GCSE Biology, there are a small number of core content diseases pupils must learn such as gonorrhoea and HIV. But, there are a wealth of other diseases that can inform them of how to keep healthy and safe whilst showing how science and medicine develop over time.

Hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E each carry with them their own interesting story that perfectly illustrates how science builds on the shoulders of those who have come before them. Personally, my favourite of these is the story of the race for a Hepatitis A vaccine at Willowbrook State School in New York. You can read the story of faeces-laden milkshakes here.

To ensure the physicists do not get envious, let’s look at one final example.

During the 1920s, after the discovery of the radioactive element by Marie Curie, there was a flurry of unregulated patent medicines. Radioactivity became the new consumer must-have. Radithor, a new medicine built on the ‘scientific’ basis of ‘radiation hormesis’, was prescribed to US socialite Eben Byers. Radithor promised to be “sunshine in a bottle” with the ability to “cure the living dead”. 1,400 doses of Radithor later, holes began forming in Byers skull and he ultimately ended up having his jaw surgically removed from the hazardous effects of consuming a radioactive liquid for practically two years.

This story is more than just interesting – it’s a crucial tool for teachers in the fight against misinformation. With pseudoscience and historical revisionism on the rise, it’s more important than ever to equip our students with critical thinking skills. By communicating accounts like Byers’, we can help guide them towards reality and steer them away from fantasy.

Creating a Map of the Hinterland

To succeed in teaching, subject knowledge is key. New teachers should focus on grasping core content and understanding the sometimes-vague curriculum specifications. Seek guidance from Heads of Departments on curriculum sequencing, and learn from teaching veterans about effective strategies for teaching core concepts and tackling misconceptions.

Whilst learning your subject many unknowingly pick up Hinterland along the way. Rosalind Franklin when teaching the discovery of DNA is a story many collect on their way when learning their curriculum; or the failure of NASA’s Mars Climate Orbiter when discussing the importance of units.

To evolve as teachers, we must continually expand our knowledge and refine our pedagogy. Reading the news, books, blogs, and websites add to our teaching toolkit and broaden our Hinterland map. We can find countless stories about science, history, mathematics, geography, and more – and it’s up to us to mould them into engaging stories that enhance our subject knowledge.

If you are one of those teachers who has a large bank of stories on your subject in the back of your mind or hidden on a spreadsheet on a drive somewhere, I encourage you to get these into the wild. Don’t keep this knowledge to yourself – let the masses benefit from your expertise and spread the wealth of stories and inspire our colleagues and students alike.

Implementing Hinterland

I have posted numerous stories that teachers can use to enrich their lessons, and when I am stories in a lesson, I am significantly more animated. There is a passion for learning about these great anecdotes but reciting them is so much fun.

Pupils find Hinterland interesting. However, it is often the case that pupils remember that Jonas Salk gave the patent for his invention of the polio vaccine away for free (Hinterland) rather than how vaccines work with the immune system to develop antibodies in the fight against future exposure to disease (core). It is a difficult line to tread but the key is to tell the students what is core content in the exams and what Hinterland I use to embolden a lesson.

Being honest about this distinction between core content and Hinterland is key to ensuring pupils focus on what must be understood and what they must revise for their exams.

When I have a Hinterland story I want to tell, I see the area where it fits into the curriculum best. Finding the lesson most relevant to teach and draw as many links as possible.

The British Doctor’s Study develops a dialogue of the importance of good data and robust study design. However, it also emboldens the dangerous effects of smoking and lung cancer. I looked at our department’s curriculum map and present the story in Health and Disease – specifically when teaching the development of new medicines. I told the tale and, as a class, we conversed about how the study was designed, why it was done in this particular way, why the size of the study mattered, and how the scientists arrived at their conclusions.

Could I have introduced this study when teaching non-communicable diseases? Of course, however, I felt much more could be gained from this story when examining it from the perspective of study design.

Is there a topic that I am going to teach that can seem a little dry? Well, when I teach bonding (core) I convey the great biographical hook of Gilbert Lewis, the inventor of Lewis dot structures, and the tales of his mystifying suicide (Hinterland). How about the extraction of metals (core)? Then there is the 2015 Mariana dam disaster in Brazil and its subsequent aftermath (Hinterland).

Using Hinterland to emphasise a specific concept or idea, or spicing up a notably vanilla topic is a great use of Hinterland, but first-class Hinterland is binding together numerous ideas to better construct connections.

When teaching Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), pupils must understand how its evidence is a validation of the Big Bang Theory and there are dozens of neighbouring core knowledge they must learn. EM waves, spectra, refraction, and imaging in space are some examples. Hence the story of how bird poop helped Arno Panzias and Robert Wilson come to the conclusion of the CMB and win themselves the Nobel Prize in 1978. Narratives like these help draw these concepts together.

Hinterland is a vital part of teaching. It is complex and brilliant! We use it to build a passion for our subject and give real-world context to the occasional cold regions of science. We focus on the core content for the need to pass exams but also foster a culture of love for intrigue that yields the scientists, engineers and nurses of the future.

Hinterland is ubiquitous. From etymology and history to biographies and eponyms. They are out there, however, they can be difficult to find.

Read the news, stay up-to-date on your subject, and subscribe to magazines, blogs and websites (shameless plug). Write them down and incorporate them into your lessons. When you have a great one, tell others in your department, share them on Twitter and WhatsApp groups or even author your own blog!

Discovering the Hinterland’s vast potential is an experience, full of exciting challenges and invaluable opportunities to invigorate the curriculum. With a great map, the Hinterland’s adventures are ours to explore, and our pupils reap the rewards. By steering our pupils through its many treasures, you can help them develop skills and gain wisdom that will last a lifetime.